A Rumble in Irvingia (aka New Brunswick)

This article appeared in a French newspaper in April 2019 but was ignored in all Canadian media because it was about the Irvings. To quote,

The family control all English-language newspapers in New Brunswick. Only the French-language daily L’Acadie Nouvelle is not a part of their empire, although they print it. They have acquired many local radio and television stations, and the University of New Brunswick presses. The conflicts of interest are grotesque: group-owned media reflect the positions of the Irving family in every area of social and industrial life. When it was reported in autumn 2018 that an explosion at the Saint John refinery had killed four people, a doctor doubted the accuracy of the company’s statement and the impartiality of the media coverage.

Dissent is rare. Teachers, civil servants and politicians fear reprisals; some have been intimidated. The 2015 dismissal of Eilish Cleary, New Brunswick’s chief medical officer of health, caused a sensation: she was investigating the use of glyphosate by Irving forestry companies. Rod Cumberland, a biologist formerly employed by New Brunswick’s natural resources department, and Tom Beckley, a professor of forestry at the University of New Brunswick, came under pressure when analysing the impact of this weedkiller on local fauna and the lack of transparency in the provincial government’s management of forests.

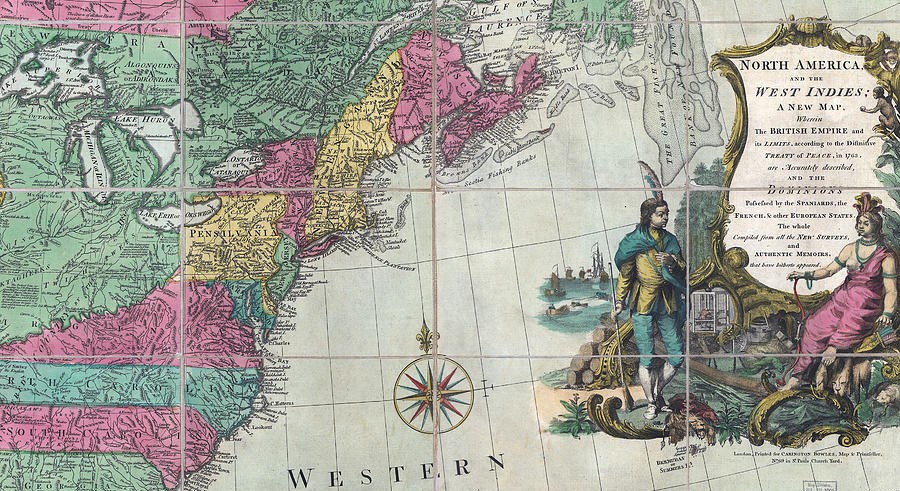

[….] As the biggest employer in the Eastern Provinces and the driving force behind industrial activity, the Irvings have made serfs of the local population. No antitrust legislation can contain their appetites. They are among the top five owners of property in North America. Canada’s National Observer (6 June 2016) calculates that the 200 or so enterprises they control have a combined capital of around C$10bn (US$7.5bn). None is listed on any stock exchange, so few details are available.

The Irving group enjoys many tax exemptions in the name of job creation. It also receives subsidies, including (by a roundabout route) through the Large Industrial Renewable Energy Purchase Program, under which the provincial power company New Brunswick Power buys sawdust and wood shavings from industrial sawmills at high prices to be used in electricity generation.

New Brunswick has also entrusted the Irvings, directly or indirectly, with managing its huge public forests, while constantly downgrading its requirements. The latest ‘Forest Management Manual for New Brunswick Crown Lands’ reduces the size of buffer zones between forests and habitable areas, authorises more clear-cutting, increases scheduled production volume and cuts protected areas from 31% to 22%. (These areas include the Irvings’ private fishing camp.) The legislation has effectively created a free trade zone for the family: the natural resources department requirements cannot be modified without their agreement.

The Irving group avoids taxes: in the 1960s it was among the first to transfer the management of its assets to tax havens, by means of accounting procedures now widespread, which allow it to use intra-group invoicing, where, for example, a subsidiary registered in a tax haven buys crude oil and resells it at a high price to another in Canada, moving as much capital as possible into the tax haven. For nearly 60 years, Canadian legislators and courts have facilitated this, allowing the Irvings to avoid contributing to the federal budget. KC Irving liked tax havens so much that he became a Bermuda resident. As the sole shareholder in the conglomerate, he directed operations at a distance through his sons, who in Canada were officially just managers.

Don Bowser, an expert on political corruption, says there is less transparency and public consultation in New Brunswick than in Kurdistan, Guatemala or Sierra Leone, despite the volume of public money involved in the exploitation of natural resources: southern hemisphere activists are fighting to find out about money that extraction companies pay to their governments, but the citizens of a province in the Canadian federation cannot get information on the taxes and licence fees that the biggest enterprise in their province pays, or how much public aid it receives. In the 1970s KC Irving justified his lack of direct engagement in politics by saying that it didn’t mix well with business, and that New Brunswick was too small for politics.

New Brunswick’s current premier, Blaine Higgs, at the head of a minority government, is a former Irving group executive who worked in the oil sector for more than 30 years.

You may have all heard about company towns. Now we got a company province. Similar phenomena once unfolded in the USA, but the intelligentsia responded through journalism and cartoons. That is when the term robber baron entered the lexicon. There is no such intelligentsia in the Maritimes. There probably never was. Oh, and the Irvings are big donors to Dalhousie University.